Ten years ago, I published a video on YouTube called “The Mystery of Jews in Japan.” In this video I highlighted common cultural points between the Japanese and the Jewish peoples. Since then, I have continued to do research. Deep dives into many academic fields were necessary. In order to make a true comparison I had to understand the history, culture, and mythology, of the Jewish people and the Japanese.

On the Jewish side, I needed to understand the evolution of a cultural group that has spread around the globe in a series of diaspora for the last 2000-3000 years. While much of Japan’s early history is conveniently “lost in a cloud of mystery.” On the Japanese side, I had to understand the mythology in the Japanese early records, the Kojiki 712 CE, and the Nihon-Shoki 720 CE. These books were written and compiled centuries after the actual events. So, I tracked the moments when early mythology crossed into actual history.

This approach led me back to the study of the Torah and Torah history. What were the original rituals and stories from the times of Moses? What was the Israelite religion and culture like before Moses? How did those rituals change over time? When did the final version of the Torah become official? The more research I did the more complicated the puzzle became.

The First Question Is When

The first question was, when could this cultural blending have taken place? If a migrant group with Jewish cultural traits helped populate Japan, they would have a very specific set of traditions. These traditions represent a kind of cultural time stamp. If these migrants arrived in Japan and had no other contact with Jews, then their culture would have evolved in isolation for thousands of years.

This scenario is similar to the “Jurassic Park” metaphor of a mosquito fossilized in amber. The mosquito not only stores its own genetic code, but those of the mosquito’s last meal. Both sets of DNA are preserved. If Israelites settled Japan and the culture evolved in isolation, the result should be a preserved form of cultural DNA. If Japanese rituals were tied to similar rituals only practiced in ancient Israel they could be used as cultural data markers, and help approximate an arrival date.

Here are some examples. The Suwa-Taisha Shrine in Nagano prefecture in Japan practices a ritual that appears to reenact the biblical story “The Binding of Isaac.” This ritual has been practiced in great detail for countless generations. Another example, the Japanese Imperial Regalia which every emperor inherits as proof of a divinity, resembles the Israelite Tabernacle. Third, the Japanese spiritual vessel the ‘Omikoshi’ carries the spirit, or Kami, of each Shinto shrine around the shrines neighborhood. In form and function this object resembles the Israelite’s Ark of the Covenant. In these cases, Japanese rituals show resemblance to Israelite rituals. The second two examples link to Japans ruling family, whose unbroken lineage dates back to the moment when Japans historical and mythical timelines first intersect, 660 BCE.

What is Jewish?

The Babylonian Empire sacked Jerusalem in 589 BCE and deported a large number of Judeans to Babylon. It was during this period the Jewish identity solidified. The exiled Judean Levite priests compiled the modern version of the Torah. They began preaching a ‘lamentation’ style of worship, meaning they longed to pray again at their Temple in Jerusalem. And the holiday of Purim was created. Purim is the holiday celebrating the Judean Queen Esther, who in 536 BCE protected the exiled Judean community from King Ahasuerus and his evil adviser Haman. If the settlers to Japan were Judeans, they would have likely had this holiday already in their pantheon. But there is no evidence so far of early Purim stories in the Japanese ritual.

One town in Japan, Mino in Gifu Prefecture, has celebrated the Purim holiday. In this case, there is a clear moment in history when the holiday was introduced. Mino is the hometown of Chiune Sugihara, a World War II diplomat, who saved six thousand Jews from the Nazi death camps. Mino periodically celebrates Purim in his honor.

If 536 BCE is the approximate start date of Purim, and there is no evidence of this festival in ancient Japan, it is feasible that contact with Japan occurred before this date. Before 589-536 BCE all the people of Hebrew descent living in Israel were ‘Israelites.’

Who Were the Israelites?

The history of the Israelites is complicated. In 930 BCE, the Hebrew tribes living in Northern Israel split from the Hebrew tribes living in the south. The northern tribes established their capital and temple in the city of Samaria. The largest tribe in the South was the tribe of Judah. The Judean capital, and temple, was in Jerusalem. One reason for the split was due to different spiritual practices. The Judeans insisted that the only place to pray to the divine patriarch ‘One God’ was at the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Israelites in the North, known as the Samarians, held a more ancestral interpretation of the ‘One God’ to mean ‘The God of All Things’. The Samarians believed in a divine union between a god and a goddess. And they practiced cultic rituals based on a ‘temporary or portable shrine’ philosophy. The Samarian Levites believed that praying at a portable shrine in the mountains was equal to praying at their temple in Samaria, because it could bring you closer to ‘The God of All Things’. The ‘temporary portable shrine’ was part of the earliest semi-nomadic Israelite tribal rituals.

The Portable Shrine

The concept of the portable shrine was reintroduced in Israel in a cultic fashion by Moses and his group of followers when they entered Israel from Egypt around 1200 BCE. In the Biblical story of the Exodus, Moses lead a group of refugees with Israelite descent to Mt. Sinai where he received God’s Ten Commandments. Moses also received directions from God on how to build The Ark of the Covenant and the Tabernacle. The Ark of the Covenant was designed to hold the tablets of the Ten Commandments and other relics. The Tabernacle was the ultimate portable shrine and allowed the refugees to pray to God no matter where they were.

The followers of Moses eventually settled in Northern Israel in the lands of Goshen and became a sizable part of the Samarian cultural group. But this region was vulnerable to enemy attack. Israelite Samaria effectively came to an end in the years 740-720 BCE when the Assyrian Empire sacked the city and forcibly removed roughly forty thousand Israelite inhabitants. The Assyrians resettled these refugees in regions around the edges of the Assyrian Empire that stretched from the Mediterranean Coast to Central Afghanistan.

The Assyrians practiced deportation with all of their defeated enemies. This caused the largest displacement of humanity the world had yet experienced. The Israelite refugees resettled in the Persian city of Susa and the expansion territory of Medes. When the Assyrian Empire fell the Judeans in Israel wondered if the Israelite refugees would return. Some most likely did. But the vast majority did not, sparking the many myths and legends of ‘The Lost Tribes of Israel.’ The mythology of the ‘Lost Tribes’ evolved over the next two thousand years. I will attempt to lay out the mythology of the ‘Lost Tribes’ in a later post.

Is It Possible?

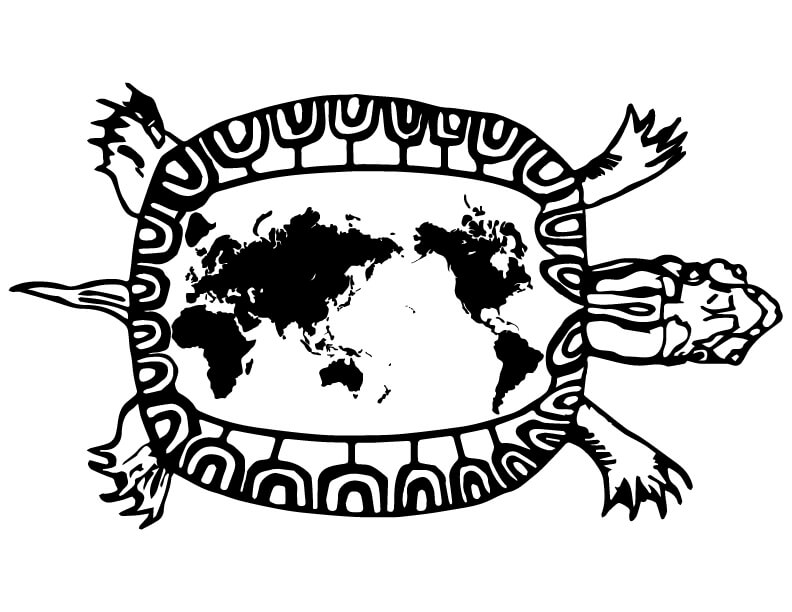

So, here we have a mass displacement of people carrying cultural markers of the Israelites in a time period of 740-720 BCE, roughly sixty years before the establishment of the Imperial Family in Japan in 660 BCE. The historical dates show a possible window of time that a connection could have occurred. The cultural rituals, the lack of other rituals, the historical timeline, all begin to line up. Could the Israelites have travelled across the Asian continent in a planned mass migration to Japan during this time? The simple answer is yes.